Nate and I didn’t cohabitate until we had decided to get married — he invited me to move in with him earlier in our relationship, but at 30, with a divorce under my belt and an apartment I loved, I just didn’t want the hassle of moving unless we were committed. My mother found this hilariously quaint.

When I did eventually pack up my stuff and move it around the corner to the duplex he’d bought when we were dating, we were still in the romantic glow of being almost-married. I found it charming and delightful to pack his lunches for work (complete with cute notes!). Though I felt busy at the time, in retrospect I had all the time in the world to browse for new and delicious recipes for dinner and shop at the farmer’s market. I don’t remember when I started washing his clothes along with mine. I also don’t remember when I stopped feeling responsible for taking out the trash.

Neither of us remembers negotiating anything about how we’d share the housework, because we didn’t.

We talked casually sometimes about who was doing which chores. We engaged in idle intellectual banter about the reasons, too, but we didn’t sit down and agree about any formal division of labor in the beginning (and by “beginning” I mean the first 5 years of our relationship). Everyone has patterns from past relationships, and things we’ve learned consciously or unconsciously from the domestic arrangements with which we were raised. Everyone also has preferences and talents, though any woman who’s ever had a haircut can tell you that it’s very difficult, maybe impossible, to disentangle preferences from socialization.

A lot of domestic patterns are connected to gender, but in the everyday ebb and flow of family life, in the organizing and prioritizing and constant renegotiating that happens in many of the marriages I’ve known, it’s a lot more complicated than old-fashioned assumptions about what people should do based on whether they’re men or women. Even for people who were raised, as I was, in steadfastly feminist households, the skills and interests we have, the ways we prioritize, and the assumptions we make about how to live together might be very different in ways that are linked to gender roles.

I love to cook, Nate loves to fiddle with technology. I have confidence and expertise when it comes to laundry, and I care a lot about how it’s done. If you ask those closest to me, they may even allege that I enjoy ironing (I will deny it).

Nobody has ever told me that I should care about having neatly-pressed clothes because I’m a woman, but several people in my life (one of them being my father, notably) invested the time to teach me how to do it well, because they thought I would need to know. Is the same true of my husband? I honestly don’t know, because he’s never cared whether his clothes were wrinkled. One might say this was just a matter of personal preference, that I am naturally more fastidious. But there’s another important difference that underlies whether we “care” about wrinkled clothes: he almost never has to prove anything by dressing a part at work every day, and in most of my jobs, I have.*

Nate tends to assume that home repairs are his job, and he has always kept tabs on our finances — sometimes, I’m embarrassed to admit, without my giving it a second thought. He has always been the one to call the guy to plow our driveway when it snows. I have mostly done the cooking and the laundry, and thus I always know what’s in our closets and our fridge. There have been many times when neither of us minded anything about these arrangements. But as domestic responsibilities multiply with children, bigger jobs, and more complex lives, what was once a private, quotidian display of affection (or at least a simple, emotionless task) can easily become a dreaded chore. Responsibilities can be part of what makes life rich and satisfying, but they’re better if you’ve consciously agreed to them.

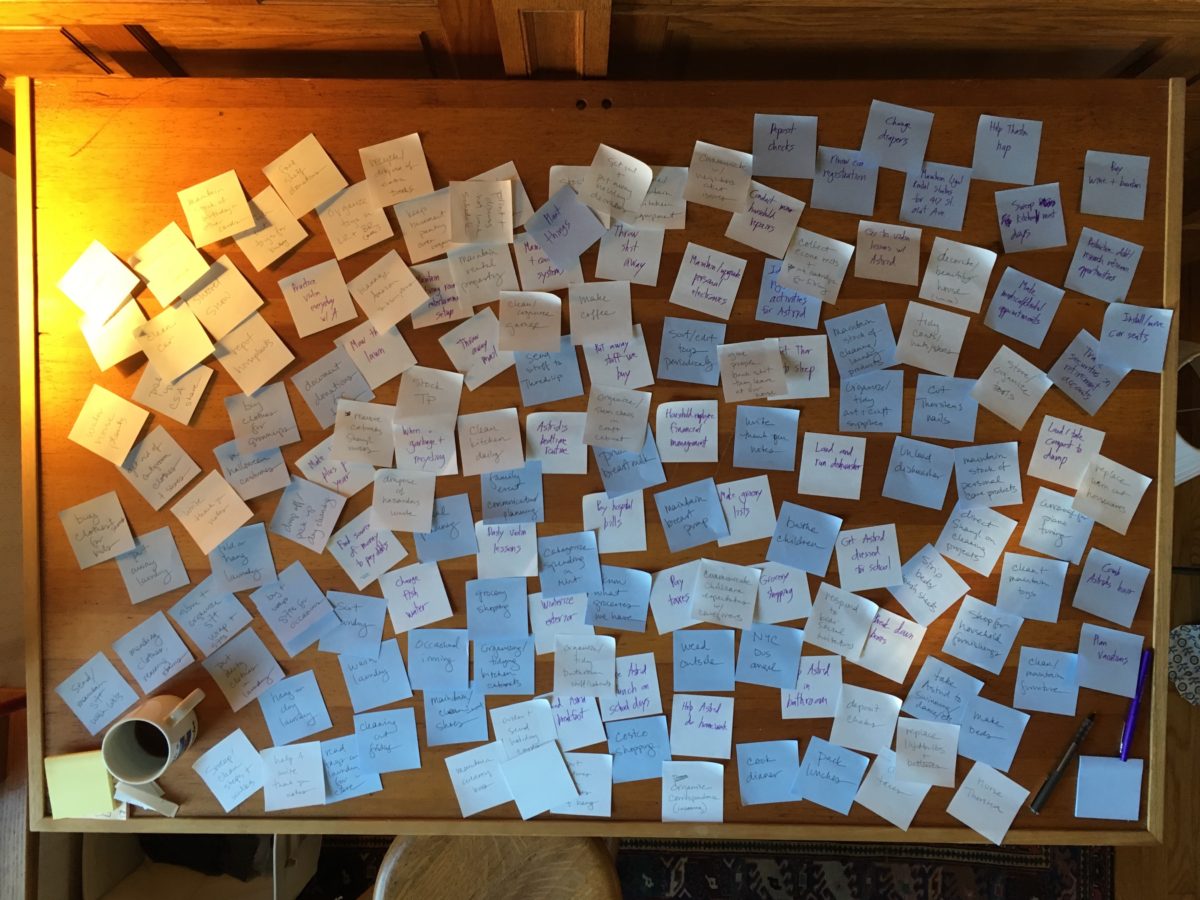

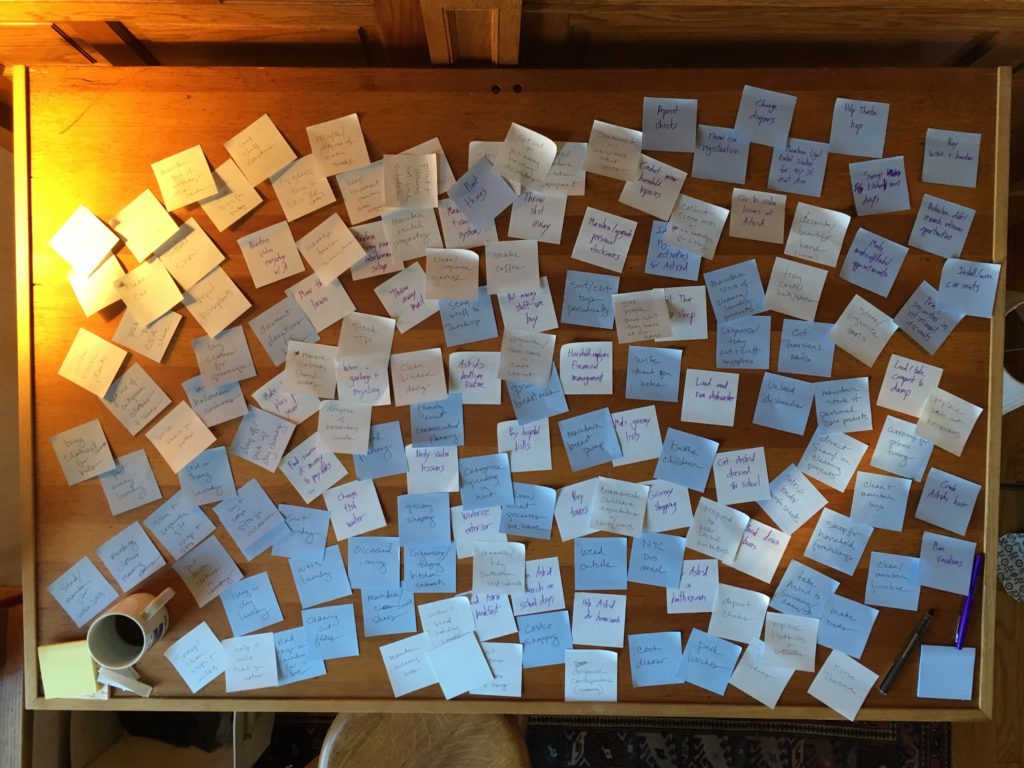

So, we sat down together to document All The Things That Need To Happen For Our Rich, Full Lives to Go Well. We used a lot of post-its.

Like most married couples (heck, probably most roommates), we have plenty of baggage about these things, but we worked hard to leave it aside. We wanted a survey, not a scoreboard. We didn’t argue about what’s important, or tally up who does more for whom, or air our guilty feelings about the things we think we ought to be doing, but aren’t. We just wrote it all down. This was extremely satisfying, and a lot more time-consuming than we expected.

* We’ll leave the unpacking of why I had to prove my worth using every conceivable tool available to me for another day, but women who have worked in offices will not need to read that future, hypothetical blog post.