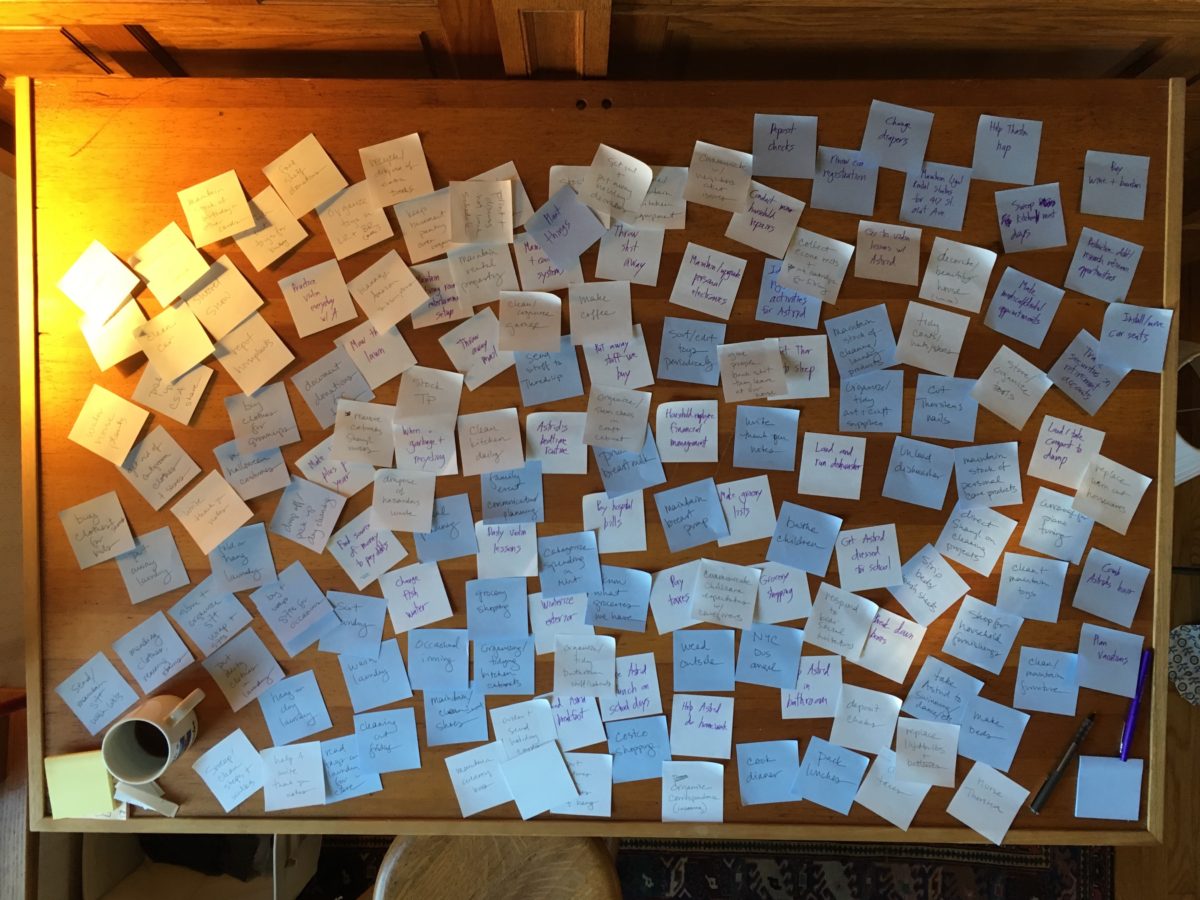

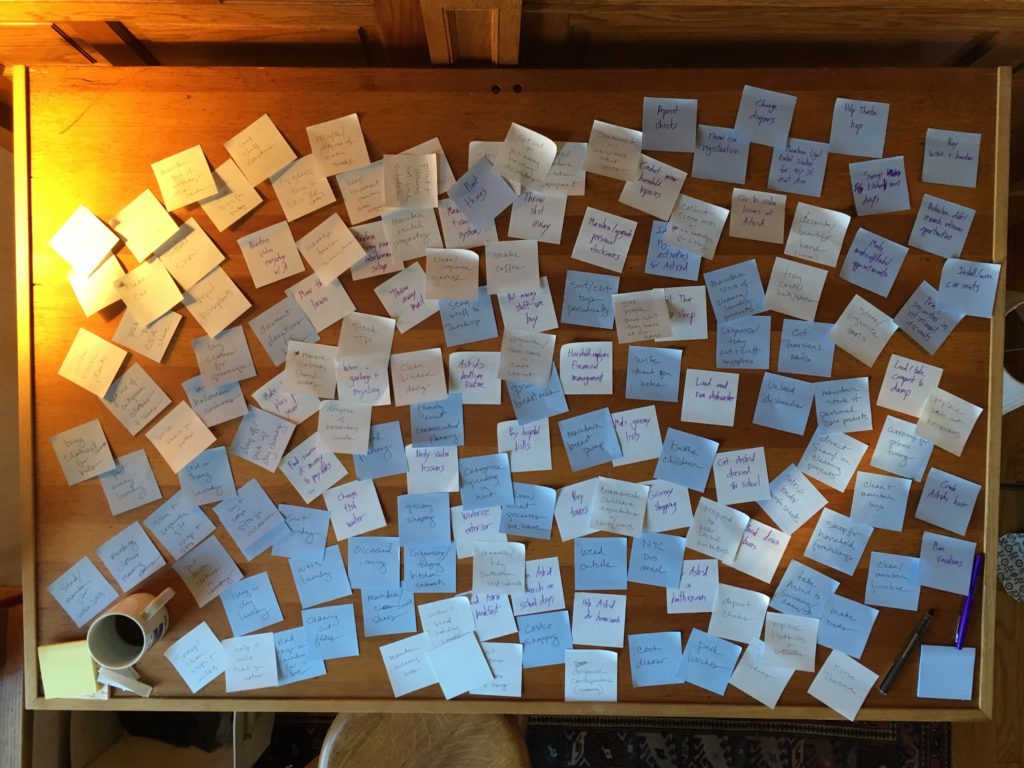

Our first step in understanding all the things that need to happen for our rich, full lives to go well was to try to write them down.

Jessica and I stood together in front of the large drafting table, notating tasks on post-its. We started slowly and then hummed along. We weren’t putting everything on the table to count who does more, but it was hard to quiet my defensive desire to itemize my tasks and prove they stack up. Secretly I was scared I’d come up short.

This feeling is a key reason to do this project.

Our shared goal with this process (and this blog) is to document all these things, and to understand who does what and why. Then we’ll be able to make decisions together about how our household runs, and the changes we need to make individually and together.

A few of my observations on the massive pile of post-its, and the process of writing them:

Emotional and domestic labor, often invisible, makes for lots of post-its.

I know this intellectually. I have even ranted about it in secret Facebook groups now and then, talking about how many men need to step up … yet I find that many tasks that Jessica put on the drafting table are not top-of-mind for me. The itemization of this work in the form of post-its makes it visible. Buying shoes for the kids. Seasonal clothing switches. Re-stocking dish soap. Creating Evites. Responding to invitations. Planning family events. We host Thanksgiving every year, sometimes for 40 guests. I make a tasty pan of roasted root vegetables (and rake in the praise for them because I’m a man that cooks a couple tasty dishes). Jessica is the mastermind of the event, planning the details and making sure everyone is comfortable, safe, sated, has a place to sit and a place to stay. This work – being the architect of the whole event – is labor that would be scary and uncomfortable for me to take on.

Isolating components is hard.

I struggled to break the tasks I feel largely responsible for into components. “Do the Taxes,” for instance, is a very big complicated deal at our house. It involves a household employee, rental property, two schedule Cs, and various filing deadlines and insurance requirements that occur throughout the year. It also, for me, involves a lot of anxiety. Should “Stress About the Taxes” be a separate post-it? I think doing the work to isolate these components might make me feel less stressed and more connected to Jessica. Tackling things together feels good.

We have some seriously gendered patterns.

We aren’t re-inventing common patterns for married cis-gender couples that I grew up around. I mow the lawn, load the dishwasher, handle finances, take out the garbage, deal with the snowplow guy, fix (or try to fix) the plumbing, and often work long hours. Jessica keeps us clothed, fed, and alive. She handles most parties and remembers to write thank you notes. She feels responsible (and takes responsibility) for the overall management of most day-to-day activities of our household. I usually drive.

We have tweaked some gendered patterns.

Jessica works outside our home, too – a lot. She owns a bookstore and serves on the city council. I do a wide range of household tasks related specifically to our children, and they view me as equally able to take care of them. I usually do Astrid’s bedtime and bath-time. I make sure the homework gets done. I am the main changer of diapers. I e-mail the 1st grade teacher. I take the kids to doctor’s appointments (though I don’t usually make them yet). Thanks to progressive paid leave policies at Carleton and MomsRising I spent a lot of time with both children when they were tiny.

For me, making post-its was a powerful step on this journey. There are a lot of things that need to happen for our rich, full lives to go well. These things, often undiscussed, have been stuck in our respective brains and driving our behavior, but not intentionally negotiated or agreed to. Now it’s all on the table.